THE SACRAMENT OF HOLY EUCHARIST

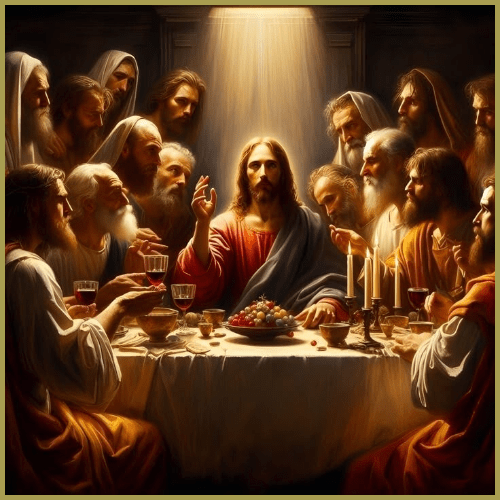

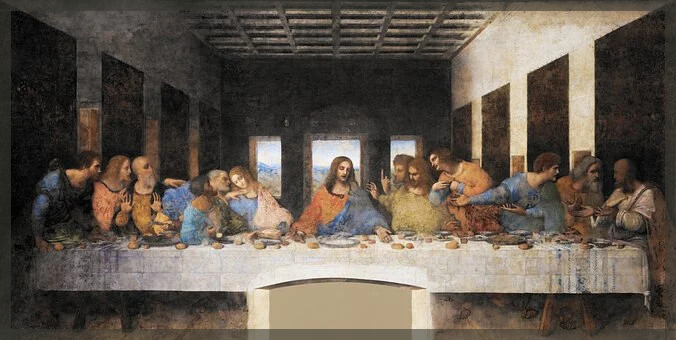

While they were eating, Jesus took a loaf of bread, and after blessing it he broke it, gave it to the disciples, and said, “Take, eat; this is my body.” Then he took a cup, and after giving thanks he gave it to them, saying, “Drink from it, all of you; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins. I tell you, I will never again drink of this fruit of the vine until that day when I drink it new with you in my Father’s kingdom.

Matthew 26, 26-29

The cup of blessing that we bless, is it not a sharing in the blood of Christ?

The bread that we break, is it not a sharing in the body of Christ?

1 Corinthians 10, 16

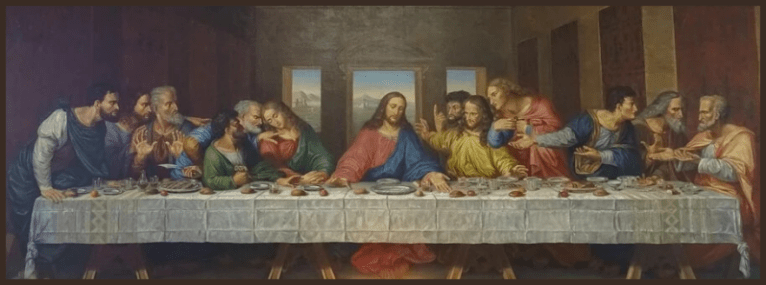

The New Testament text concerns a significant moment in the Christian tradition, particularly within Catholic dogma, namely the institution of the Eucharist. This pivotal passage is found in Matthew 26:26-29, where Jesus shares a final meal with His disciples before His crucifixion. Within this context, Jesus takes the bread, blesses it, breaks it, and gives it to His disciples, saying, “Take, eat; this is my body.” He then takes a cup of wine, gives thanks, and offers it to them with the proclamation, “Drink from it, all of you; this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins.”

This text encapsulates key theological concepts central to Catholic beliefs regarding the Eucharist, which is celebrated during Mass. Catholics hold that, through the process of transubstantiation, the bread and wine become the actual Body and Blood of Jesus Christ. This belief asserts that the elements undergo a real and complete change at the level of substance while retaining their outward appearances. The importance of the phrases “This is my body” and “This is my blood” is profound; they signify not merely a symbolic representation but a literal transformation that underscores the Eucharist’s deep sacramental nature.

Moreover, Jesus refers to His blood as the “blood of the covenant,” linking His sacrifice to Israel’s ancient covenantal traditions. In Catholic teaching, the New Covenant represents the fulfillment of the Old Covenant, established through the Law and the prophets. This New Covenant signifies a transformative relationship between God and humanity, mediated through the sacrifice of Jesus, who offers reconciliation and salvation. The Eucharist thus becomes a vital sacrament in Catholic worship, a moment of communion not only with Christ but also with one another within the body of the Church, reflecting the communal aspect of faith and divine grace.

The act of taking and sharing bread and wine represents not only physical nourishment but also spiritual communion. This rite serves as a memorial of Jesus’ sacrifice and a way to share in His divine life. Catholics participate in the Eucharist to remember Jesus’ passion, death, and resurrection, which are foundational to their faith. The passage highlights that Jesus’ blood is “poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins.” The Catholic Church teaches that the Eucharist is a source of grace and forgiveness, allowing the faithful to receive divine mercy and be reconciled with God. This sacrament is deeply connected to the theme of salvation. When Jesus states, “I will never again drink of this fruit of the vine until that day,” He expresses a future hope that reflects an eschatological perspective regarding the fulfillment of God’s kingdom. Catholics view the Eucharist as a foretaste of the heavenly banquet with Christ, which reinforces their hope for eternal life.

The passage from 1 Corinthians 10:16 underscores the Eucharist’s profound significance in Catholic teaching, linking the Last Supper to the communal nature of the Christian faith. In this scripture, St. Paul articulates that the Eucharist is not merely a ritual or a symbolic act; rather, it represents a profound and transformative participation in the sacrifice of Jesus Christ. The reference to the “cup of blessing” alludes to the chalice used during the Eucharistic celebration, which, according to Catholic doctrine, becomes the actual blood of Christ through the priest’s consecration. This act is a central tenet of Catholic belief, reflecting the mystery of transubstantiation – the transformation of the substances of bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ while retaining their outward appearances.

Similarly, the phrase “the bread that we break” signifies the Eucharistic bread, which is understood to become the genuine body of Christ. This belief underscores the intimate connection that Catholics hold with Christ during the Mass, as they participate in a sacred meal that commemorates the Last Supper. The celebration of the Eucharist fosters a sense of unity among the faithful, reinforcing the idea that they are not only partaking in a ritual but also joining together as one body in Christ. This communal aspect signifies that the shared experience of the Eucharist strengthens the bonds of the Christian community and deepens the spiritual relationship with God, reminding believers of the central role of Christ’s sacrifice in their faith journey.

The notion of “sharing” in the body and blood of Christ embodies the Catholic understanding of communion as a profound communal act that symbolizes and fosters unity among the faithful, both with Christ and with one another. This concept is deeply rooted in the dynamics of the Last Supper, where Jesus instituted the Eucharist, engaging His twelve disciples in this pivotal covenantal meal and inviting them to partake in His singular sacrifice for humanity. The Last Supper itself occupies a foundational role in Catholic liturgical practice, observed with great reverence during Holy Thursday’s Mass of the Lord’s Supper, which commemorates the institution of the Eucharist and the church’s call to serve one another in love.

The celebration of the Eucharist is central to Catholic worship and serves multiple purposes: it acts as a memorial of Christ’s passion, death, and resurrection, while also functioning as a sacred channel through which believers receive divine grace, spiritual sustenance, and nourishment for their unique faith journeys. It is through this sacrament that the Catholic Church believes the presence of Christ is made manifest among the community, reinforcing the bonds of fellowship among believers and their commitment to live out the teachings of Christ in their daily lives.

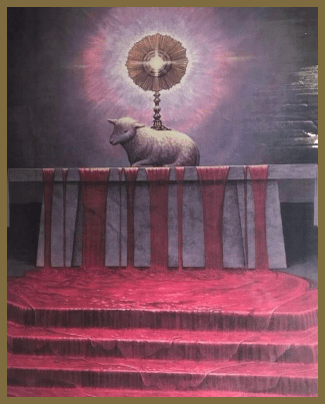

The event of Christ offering Himself as the Passover lamb during the Last Supper marks the foundation of the Eucharist celebration for New Covenant believers. On that transformative night, coinciding with the Jewish Passover, Jesus redefined the traditional Passover meal, which typically included a sacrificial lamb, to convey a deeper spiritual significance. To grasp the magnitude of this shift, we must examine the structure of the Last Supper itself, which occurs within the context of the Passover Seder. During this ritual meal, Jesus presides over a gathering with His apostles, who are required to partake of four cups of wine as part of the Seder, each cup representing a different aspect of redemption.

Matthew’s Gospel begins its account during the serving of the third cup, known as the Berekah or the “Cup of Salvation.” This choice is significant, as Jesus, aware of His impending sacrifice, connects this moment to His role as the Passover lamb. In Matthew 26:29 and Mark 14:25, He speaks of not drinking again from the fruit of the vine until He drinks it anew in His Father’s kingdom, emphasizing the eternal nature of the redemption He is about to accomplish.

In addition, the Apostle Paul refers to this third cup as the “Cup of Blessing” in 1 Corinthians 10:16, thereby drawing a direct link between the Seder meal and the sacrament of the Eucharist. This connection illustrates that the consumption of the third cup presents the Paschal sacrifice of Christ, the Lamb who was slain for our sins, as prophesied in Isaiah 53:7 and heralded by John the Baptist in John 1:29, where he declares Jesus to be the “Lamb of God.” This profound moment reiterates the continuity between the Jewish Passover and the Christian understanding of salvation through Christ’s sacrifice, highlighting the significance of the Eucharist as a celebration of that redemptive act.

In the Passover Seder, Jesus notably omits the fourth cup, known as the Hallel, or “Cup of Consummation.” This omission is deeply significant, as it connects the Eucharistic sacrifice represented in the Seder to Christ’s ultimate sacrifice on the cross. Both events—the Last Supper and the crucifixion—are intertwined, illustrating a singular act of salvation. The Last Supper serves not only as a ritual meal but also as a prophetic foreshadowing of Jesus’ crucifixion.

As part of the Jewish tradition, the fourth cup symbolizes the completion of the Passover and the fulfillment of God’s promises. Therefore, this cup remains unconsumed during the Last Supper, indicating that the sacrifice is not yet complete at that moment. It is not until Jesus is on the cross, where He declares, “It is consummated” (Jn 19:29, 30), that He finally consumes the fourth cup through the sour wine offered to Him, signifying the completion of His redemptive work. This profound connection emphasizes that the Last Supper and the crucifixion are not separate events but rather two parts of the same divine plan for humanity’s salvation.

On the cross, Jesus was offered sour wine on a hyssop branch, a detail that resonates deeply with biblical traditions. In Exodus 12:22, the Israelites used hyssop to sprinkle the lamb’s blood on their doorposts, thereby securing divine protection against the plague. This act represents the sacrificial lambs whose blood was shed, a poignant precursor to Christ’s ultimate sacrifice. Furthermore, hyssop was used by the priests under the Old Covenant in sacrificial offerings, signifying purification and atonement. This connection deepens our understanding of Christ’s sacrifice; it links him to the lambs that were slaughtered and consumed during the Seder meal, a central ritual in Jewish Passover commemorating the Exodus from Egypt.

During the Seder, the Cup of Consummation marked the climax of the meal, during which wine is consumed as a symbol of joy and the fulfillment of the covenant. Thus, the narrative of Christ’s sacrifice intertwines with these deeply rooted traditions, illustrating that his offering of himself began in the upper room, where he instituted the Eucharist, and was consummated on Mount Golgotha, where he willingly laid down his life, transcending the old covenant with the establishment of a new and everlasting covenant through his blood.

The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass in the Catholic Church serves as a profound and timeless re-presentation of Christ’s singular sacrifice on Calvary. This sacred liturgy, often referred to as the Lord’s Supper or Seder meal of the New Covenant, allows the faithful to experience the reality of Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection as perpetually present. It serves as a visible sign of the eschatological marriage feast in heaven, as depicted in Revelation 19:9, which describes the blessed union between Christ and His Church.

St. Paul underscores the importance of celebrating this Eucharistic feast in his first letter to the Corinthians, stating, “Therefore, let us celebrate the festival, not with the old yeast, the yeast of malice and evil, but with the unleavened bread of sincerity and truth” (1 Cor 5:8). This passage highlights not only the call to participate in the Eucharist but also emphasizes the need for inner purity and sincerity when approaching this sacred rite.

In essence, partaking in the Eucharist means worthily consuming the flesh of the Lamb of God and drinking His blood in the Blessed Sacrament. This sacramental participation is integral to achieving holy communion with God and fully reaping the spiritual fruits of Our Lord’s ultimate sacrifice, as elaborated in 1 Corinthians 11:17-22. Here, Paul cautions the faithful to approach the Eucharist with reverence and discernment, ensuring that they are aligned with the truth and grace of God’s covenant. In doing so, believers not only acknowledge Christ’s sacrifice but also embrace the transformative power it holds for their lives.

Hence, the Lord’s Supper isn’t just a symbolic memorial meal, as most Protestants contend, but a marriage feast that marks God’s establishment of the New Covenant in which the Eucharist makes Christ’s one eternal sacrifice present. Scripture confirms this truth in the words of consecration – “Do this in remembrance of me” – used by Jesus in the Last Supper: touto poieite tan eman anamnasin (Luke 22:19; cf. 1 Corinthians 11:24-25). Our Lord says, “Offer this as a memorial sacrifice.” The Greek verb poiein (ποιεῖν) or “do” is used in the context of offering a sacrifice, where, for instance, in the Septuagint, God uses the same word poieseis (ποιέω) regarding the sacrifice of the lambs on the altar (Exodus 29:38-39). The noun anamnesis (ἀνάμνησις), “remembrance,” also refers to a sacrifice that is actually made present in real time by the power of God in the Holy Spirit, as it recalls the actual event (Hebrews 10:3; Numbers 10:10).

The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass transcends being merely a memorial to a historical event; it represents a profound mystery in which a past event is made present in the current moment. In this context, Christ’s Eucharistic sacrifice serves as a living memorial, a constant reminder of the redemptive work that our Lord has accomplished for humanity and continues to actualize through his singular and timeless sacrifice. This understanding emphasizes that the Eucharist is not merely a recollection of a completed event, but a dynamic participation in the ongoing reality of Christ’s sacrifice.

While the crucifixion itself remains a definitive historical moment, the significance of Christ’s single sacrifice extends beyond that moment into the present. Each celebration of the Mass reopens that moment, allowing the faithful to experience the grace and mercy of that act of love anew. Through the Sacrament of the Holy Eucharist, believers participate in this eternal reality in which Christ’s self-offering on the cross is uniquely and continuously made present, inviting all to draw deeper into the mystery of salvation.

We read in Leviticus 24:7: ‘By each stack put some pure incense as a memorial portion to represent the bread and to be a food offering presented to the LORD.’ The Hebrew word “memorial,” in the sacrificial sense, is the feminine noun azkarah (אַזְכָּרָה), meaning “to actually make present.” There are many instances in the Old Testament where azkarah refers to sacrifices that are currently being offered, and thus are present in time (Leviticus 2:2, 9, 6:5; 16:5-12; Numbers 5:26; 10:10). These are the same sacrifices that are being offered in memory at this time. Jesus’ command for us to provide the bread and wine (transubstantiated into his body and blood) as a memorial offering shows that the sacrificial offering of his body and blood is made present in time over and over again while serving as a reminder of what he has accomplished for us through his one, single sacrifice of himself. Thus, the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass is sacramentally a re-presentation of Christ’s sacrifice on the cross, which began at the Last Supper and historically occurred on Calvary.

Sadly, Protestants argue in disbelief that Jesus is speaking metaphorically about eating his flesh and that the bread only symbolizes his body. However, the Greek verbs used in John 6 (The Bread of Life Discourse) render their interpretation implausible. Throughout John 6:23-53, the Greek text uses the verb phago (φάγω) nine times. This verb means to literally “eat” or physically “consume.” Jesus repeated himself this often because of the Jews’ disbelief. In a sense, he was challenging their faith in him while driving home a vital point. In fact, many of his disciples deserted him since they knew he was speaking literally and thought he was mad. For this reason, Jesus uses an even more literal verb describing the food consumption process (John 6: 54, 55, 56, 57). This is the verb trogo (τρώγω), which means to “gnaw,” “chew,” or “crunch.” Although phago may be used metaphorically, trogo is never used symbolically.

Anyway, for further clarification, Jesus says, “For my flesh is food indeed, and my blood is drink indeed” (Jn 6:55). Jesus is responding to those who refused to believe in what he was saying. Additionally, when Jesus institutes the Eucharistic sacrament at the Last Supper, He says, “This is my body and blood” (Matthew 26:26; Mark 14:22; Luke 22:19-20). The Greek phrase is “Touto estin to soma mou.” So, what our Lord means to say is, “This is really or actually my body and blood.” St. Paul uses the same phraseology in his First Letter to the Corinthians 11:24. Paul does reaffirm that “the cup of blessing” and “the bread of which [the Corinthians] partake” is “actual” participation in Christ’s body and blood” (1 Corinthians 10:16). The Greek noun koinonia (κοινωνία) denotes a “participation” that isn’t merely symbolic.

Moreover, the Greek text in John’s Gospel uses sarx (σάρξ), which literally means “flesh.” The phrases “real food” and “real drink” contain the adjective alethes (ἀληθής), which means “really” or “truly” (John 6:55). This adjective is used on occasion when there is doubt concerning the reality of something, in this case, which is Jesus’ flesh really being food to eat and his blood really being something to drink for everlasting life. Jesus is assuring his doubters that what he literally says is true. The Apostles refused to desert Jesus after listening to their Master’s discourse. They attended the Seder meal with him, on which occasion, they consumed the flesh of the sacrificed Lamb of God and drank his blood just as the Jewish people ate the flesh of the sacrificed lamb and were sprinkled with its blood for the forgiveness of sin (Exodus 12:5-8; 24:8).

EARLY SACRED TRADITION

Justin Martyr, First Apology, 66

(A.D. 155 )

“For not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like

manner as Jesus Christ our Saviour, having been made flesh and blood for our

salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the

prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are

nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh.”

Irenaeus, Against Heresies, V:2,2

(c. A.D. 190)

“He acknowledged the cup (which is a part of the creation) as his own blood,

from which he bedews our blood; and the bread (also a part of creation) he

affirmed to be his own body, from which he gives increase to our bodies.”

Basil, To Patrician Caesaria, Epistle 93

(A.D. 372)

“It is good and beneficial to communicate every day, and to partake of the holy

body and blood of Christ. For He distinctly says, ‘He that eateth my flesh and

drinketh my blood hath eternal life.’ And who doubts that to share frequently in

life, is the same thing as having manifold life. I, indeed, communicate four times a

week, on the Lord’s day, on Wednesday, on Friday, and on the Sabbath, and on the

other days if there is a commemoration of any Saint.”

Ambrose, On the Mysteries, 9:50

(A.D. 390-391)

“Perhaps you will say, ‘I see something else, how is it that you assert that I receive

the Body of Christ?’ And this is the point which remains for us to prove. And what

evidence shall we make use of? Let us prove that this is not what nature made, but

what the blessing consecrated, and the power of blessing is greater than that of

nature, because by blessing nature itself is changed…The Lord Jesus Himself

proclaims: ‘This is My Body.’ Before the blessing of the heavenly words another

nature is spoken of, after the consecration the Body is signified. He Himself speaks

of His Blood. Before the consecration it has another name, after it is called Blood.

And you say, Amen, that is, It is true. Let the heart within confess what the mouth

utters, let the soul feel what the voice speaks.

“I am the bread of life; whoever comes to me shall not hunger,

and whoever believes in me shall never thirst.”

John 6, 35

PAX VOBISCUM

Leave a comment